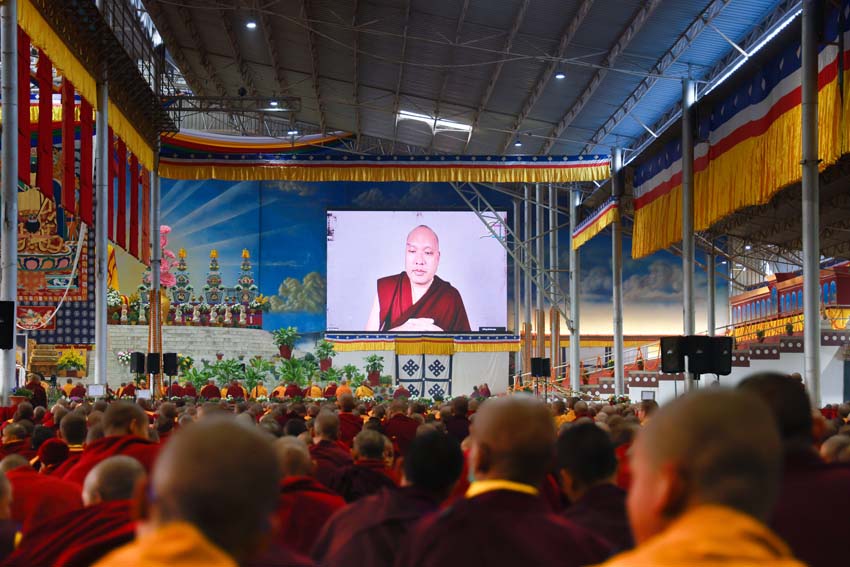

Pre-Monlam Teachings

22 December 2025

As a preliminary to the profound empowerment of Vairocana Abhisaṃbodhi [The Complete Awakening of Vairocana] bestowed by Drung Goshir Gyaltsab Rinpoche, His Holiness the Gyalwang Karmapa offered an introductory teaching on the history of this tantra and the Caryā tantra class. He opened this pre-Monlam teaching session expressing his great appreciation for Goshir Gyaltsap Rinpoche and with warm greetings to the entire audience. In this session he gave some insights into the history and the development of tantra in general, however, the extensive exposition on this subject is offered during his online Mar Ngok Summer teachings which stretch over several years.

Though the Karma Kamtsang lineage has numerous tantras, the Caryā class of tantra within our lineage is still incomplete. It is for this reason that His Holiness decided to ask Gyaltsab Rinpoche who had previously received the empowerment of The Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana from Trichen Rinpoche. He received it with great care and preparation, entering a week-long retreat prior to receiving it.

The Emergence of Tantra

From the 7th to the 8th century, in India and its surrounding regions, the dhāraṇīs, mantras, visualization practices, peaceful and wrathful rituals and so forth that had gradually developed within the Mahāyāna—began to show signs of systematic organization under uniform structures. With this, a new mysterious and wondrous but mostly hidden tantric aspect began to take form in the Mahāyāna.

Both the Madhyāmaka and Yogācāra (Cittamātra or Mind Only) schools came to rely on this extraordinary tantric meditation method and it was decided that the ultimate result of complete Buddhahood could be achieved only through this method. Such practices came to represent the ultimate step toward the realization of Mahāyāna philosophical tenets. The outstanding Mahāyāna scholars of that period, while holding Madhyāmaka, Yogācāra or the Tathāgatagarbha [Buddha Nature] views philosophically, began to employ tantric methods in their meditation practice.

While we accept that the Mahāyāna developed into tantric tenets, the exact manner of its evolution is not entirely clear to us at present. But it is clear that the features of tantra must not be viewed merely in terms of the development of Mahāyāna thought, but rather as a hidden, mysterious practice system that already existed within the Mahāyāna prior to this period. Then, somewhere around this point in history, it developed through broadening and systemizing the many previously established mystical and wondrous methods.

The emergence of The Abhisambhodhi of Vairocana and Vajradhātu Tantra [Vajra Expanse Tantra] marked the beginning of a new chapter in the tantric teachings. According to Japanese tradition, these two are called "pure tantra" (mitsumitsu). "Pure" is a designation made in contrast to the unorganized or fragmentary tantras, uncollected dhāraṇīs, etc., that came before, designated as “mixed tantra” (zōmitsu).

In comparison, in India and Tibet there are various methods of classifying tantric texts. For example, what the Japanese designate as “mixed” or “fragmentary” tantra corresponds to the class of Kriyā (Action) tantra in Tibet. The Abhisambhodhi of Vairocana is classified as the Caryā (Conduct) tantra class in Tibet. The Vajra Expanse is classified as Yoga tantra and the tantric texts which followed it, developed subsequently as Anuttarayoga tantra (Unexcelled Yoga tantra).

The methods of classifying tantric texts in Japan, India and Tibet are primarily based on their subject matter, but sometimes include classifications based on their significance. Another possible classification among Japanese scholars is based on chronological order: the "early-period tantra," "middle-period tantra" and "late-period tantra". Scholars prefer to place The Abhisambhodhi of Vairocana and the Vajra Expanse in the "middle-period tantra".

Tantra Classes

There are innumerable tantras in the vast Secret Mantra system which can be classified in many ways; commonly between two and seven, but the most widespread tradition in Tibet is the classification into four classes. The Nyingma tradition teaches the nine vehicles: Upa, Yoga, etc. But all the others—Kagyü, Sakya, Gelug, Jonang, Zhalu and so forth—primarily use the fourfold division. His Holiness attributes this to the verses from the explanatory tantra of Hevajra, called the Vajrapañjara [Vajra Dome.; Tib. རྡོ་རྗེ་གུར།] which read:

For inferior beings, the Kriyā tantra;

For those beyond Kriyā, Caryā;

For supreme beings, Yoga tantra;

And for those beyond that, the Unexcelled [Anuttara].

The reason for making this division is also stated in the Sampuṭa, the explanatory tantra common to Hevajra and Cakrasaṃvara:

Smiling, gazing, holding hands,

And embracing—these four types

Abide as four tantras in the manner of insects.

Since there are four different ways of taking desire onto the path, there are also four corresponding tantras. The Gelugpas consider this the main reason behind the fourfold division.

Alternatively, the Glorious Sakyapa tradition primarily explains the origin of the fourfold division thus:

in Kriyā there is no self-generation;

in Caryā there is self-generation but no inviting of the wisdom beings;

in Yoga tantra there are both self-generation and inviting the wisdom beings, but at the end, the wisdom beings are requested to depart; and

in Unexcelled Yoga tantra there is self-generation and no requesting the wisdom beings of the self-generation to depart.

Some other reasons for establishing the fourfold division are:

With respect to the castes:

Unexcelled Yoga tantra corresponding to the common caste,

Yoga tantra corresponding to the royal caste,

Caryā tantra corresponding to the minister caste, and

Kriyā tantra corresponding to the brahmin caste

With respect to the afflictions:

Unexcelled Yoga tantra is taught for the purpose of taming those with desire,

Caryā tantra for the purpose of taming those with anger,

Kriyā tantra for the purpose of taming those with delusion, and

Yoga tantra for the purpose of taming those of indeterminate type.

However, Je Tsongkhapa and others rejected this classification, saying it is not necessarily so.

Though classifications are many, the fundamental hierarchy—from Kriyā as the lowest, then Caryā, Yoga and Unexcelled as the highest—is widely known and accepted in Tibet. Following that sequence in one’s own practice is taught to be very important. The Hevajra Tantra explicitly states: “Once you know all stages of vehicles, then Hevajra is taught.” This means that one should follow it like a ladder, proceeding through the three vehicles, the four philosophical tenets and the four tantra classes.

Je Tsongkhapa also states in his The Essence of True Eloquence (Tib. ལེགས་བཤད་སྙིང་པོ།):

One who does not know the manner of the path of the lower three tantra classes,

Though deciding that Unexcelled Yoga tantra

Is supreme among all tantra classes,

I have clearly seen that it amounts to mere assertion.

In order to understand the profound points of these, one needs to understand the lower classes of tantra first through study and practice.

In the Great Exposition on Tantra (Tib. སྔགས་རིམ་ཆེན་མོ།), in the section on Caryā tantra, he states:

If one does not know in detail the distinctive features of what kind of path exists in these lower tantra classes, it is because one will not know the uncommon paths of the higher ones.

Understanding the hierarchy of their importance comes from the practice which follows that hierarchy. This approach allows one to reach the higher paths. One might want to jump straight into the Unexcelled, thinking that it is so important and famous, but it might become very difficult to actually get there. The crux of the matter here is: in order to practice the higher, we need to practice the lower first.

The Significance

When the congregation recited the verses for the tea offering, the Karmapa remarked that we have the tradition of offering to the deities of the four classes by reciting:

The four tantra classes—Kriyā, Caryā, Yoga and Unexcelled Yoga —Whatever the Teacher himself taught,

To the outer, inner, and secret

Yidam deities I make offerings.

But, at present, we don’t have complete practices of all of these. Among the Kriyās, we only have Akṣobhya and in the Yoga class, only the Sarvavid [All-Knowing Vairocana; Tib. ཀུན་རིག།]. In the past we practiced all four and now it is very important that we understand that there is a great lacuna remaining in the way of pith instructions. It is documented how the earlier Kadampa masters earnestly desired to receive the empowerment of Caryā tantra The Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana, like a thirsty person desires water.

In terms of the Buddhist history of the world, formerly in China and later in Japan and elsewhere, the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana was regarded as among the most important of the Secret Mantra scriptures. There are many dhāraṇīs and mantras taught within the Vinaya and Sūtra collections. These are mainly methods for accomplishing common siddhis, such as pacifying harm and bringing about auspiciousness, overcoming enemies—all for the benefits of this lifetime. But, the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana, the Vajraśekhara [Vajra Peak; Tib. རྒྱུད་རྡོ་རྗེ་རྩེ་མོ།] or Vajra Expanse were considered as the Secret Mantra scriptures with a complete path for accomplishing the supreme siddhi. Seeing that these tantras hold such importance, there is no doubt that maintaining their lineage will bring about manifold benefits.

For these many reasons the Gyalwang Karmapa has asked Drung Goshir Gyaltsab Rinpoche to please bestow the empowerment of the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana at the Kagyu Monlam, and this is a great fortune for us, he says. He also expressed his hope of receiving the Vajra Expanse in the future as well—thus reinforcing the teachings in general.

The Transition into Systemised Tantra

The development from early-period tantra to middle-period tantra was gradual and it is difficult to clearly distinguish their divide. Roughly speaking, in the early-period the scattered mantras and dhāraṇīs taught during the Buddha‘s lifetime were used. Their main purpose was to obtain happiness in this life, centered on worship rituals like Mārīcī or the Sitātapatrā [White Parasol; Tib. གདུགས་དཀར་པོ་ཅན།], and many others, like the rituals in the Vinaya for healing snake bites. At that time, although maṇḍalas, mudrās, dhāraṇīs, mantras, visualization practices and so forth existed, there were no organized relationships among them. Maṇḍalas were taught but their forms were still evolving.

In comparison, in middle-period tantra as exemplified by The Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana and the Vajra Expanse, the attainment of buddhahood was the ultimate goal. There was profound integration of Mahāyāna philosophical thought and tantric methods. During practice as well, the yoga of the three secrets of body, speech and mind was emphasised, and the deities were incorporated into the maṇḍala based on specific principles—with profound reason and many complexities of the organisation of all these elements.

There is much debate in Tibet over the classification of some practices which are contained in the sūtras but indeed have many tantric elements, such as the Medicine Buddha. Scholars debate whether these should be called tantras or sūtras, as it very difficult to distinguish. If we apply the classification from the Japanese tradition here, the organisation of these falls into place more easily. Many such practices with tantric elements exist not only among the Mahāyāna but also the Foundation Vehicle sūtras, like the Mahāmāyūrī Sūtra [The Great Peahen Sutra] but they don’t teach the full path to complete Buddhahood. That occurred during the middle-period tantra, according to Japanese scholars.

The Four Classes as Taught in Tibetan Tradition

Why is the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana included in the Caryā class? The Compendium of the Wisdom Vajra [Tib. ཡེ་ཤེས་རྡོ་རྗེ་ཀུན་ལས་བཏུས་པ།] states:

That which is to be accomplished and that which accomplishes by thoroughly performing the hand mudrās and characteristics of visualization objects of Kriyā tantra, which teaches the various extensive activities of action, abides in Caryā tantra.

The meaning of this is: Kriyā [Action] tantra extensively teaches the various external activities of body and speech through hand mudrās, characteristics of visualisation objects, cleanliness and so forth. Caryā [Conduct] tantra combines these activities with the internal practice of the mental meditative absorptions which accord with Yoga tantra. The Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana is the primary example of this.

Examples of Caryā Tantras

Apart from the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana, the other main text identified as Caryā tantra is the Vajrapāṇi Abhiṣeka Tantra [Empowerment of Vajrapani Tantra; Tib. ཕྱག་རྡོར་དབང་བསྐུར།]. Some scholars teach that within Caryā tantra there are three families: the Tathāgata family, the Padma family and the Vajra family. Among these, the tantra of the Tathāgata family is the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana; the tantra of the Padma family was not translated into Tibetan; and the tantra of the Vajra family is the Empowerment of Vajrapāṇi Tantra.

The Sakya master Ngorchen Kunga Zangpo held that all texts that explicitly teach self-generation but do not teach inviting the wisdom beings are Caryā tantra. Therefore, he held that there are many more Caryā tantras than just that one. In his General Meaning of Caryā Tantra [Tib. སྤྱོད་རྒྱུད་ཀྱི་སྤྱི་དོན།], he states that there are about nine pure Caryā tantras in Tibet. Along with the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana, he includes: Mañjuśrī Mūla Tantra [Root Tantra of Manjushri; Tib. འཇམ་དཔལ་རྩ་རྒྱུད།], Siddhaikavīra [Single Hero’s Accomplishment; Tib. དཔའ་བོ་གཅིག་ཏུ་གྲུབ་པ།], Mārīcī Kalpa Tantra [Tantra of the Practice of Marichi; Tib. ལྷ་མོ་འོད་ཟེར་ཅན་གྱི་རྟོག་པ།], Acala Kalpa Tantra [Tantra of the Practice of Achala; Tib. ཁྲོ་བོ་མི་གཡོ་བའི་རྟོག་པ།] and Bhūta Ḍāmara Tantra [Tamer of Spirits Tantra; Tib. འབྱུང་པོ་འདུལ་བྱེད་ཀྱི་རྒྱུད།] which is also found in the Knowing One Liberates All [Tib. གཅིག་ཤེས་ཀུན་གྲོལ།] collection by the 9th Karmapa Wangchug Dorje, making this latter Caryā tantra a part of the Kamtsang tradition.

However, as stated in the Synonyms for the Names of the Four Tantra Classes [Tib. རྒྱུད་སྡེ་བཞིའི་མིང་གི་རྣམ་གྲངས།] composed by Longdol Lama Ngawang Lozang:

The Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana in twenty-six chapters,

Its later tantra in seven chapters,

And the Empowerment of Vajrapāṇi in twelve volumes

— Apart from these, Caryā tantras were not translated into Tibetan.

Accordingly, the commonly known main Caryā tantras are these two: the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana and the Empowerment of Vajrapāṇi.

The Chinese Translation

In Chinese, the same texts otherwise known as tantras, are often called sūtras. The full title of the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana is The Dharma Teaching Called the Blessed Lengthy Manifestation of the Abhisambhodhi of Vairocana, the Powerful King of All Sūtras [Tib. རྣམ་པར་སྣང་མཛད་ཆེན་པོ་མངོན་པར་རྫོགས་པར་བྱང་ཆུབ་པ་རྣམ་པར་སྤྲུལ་པ་བྱིན་གྱིས་རློབ་པ་ཤིན་ཏུ་རྒྱས་པ་མདོ།]. Although no Sanskrit manuscript has been found to date, we can understand portions of its content based on quotations in other texts and commentaries. According to historical records, the earliest translation of the Abhisambhodhi of Vairocana was in the 12th year of Kaiyuan (724 CE), translated into Chinese by the Indian master Śubhākarasiṃha with Yixing serving as scribe. Its original manuscript is said to be the belongings of Wuxing who passed away in India at the end of the 7th century. The sūtra has a total of six fascicles, with the first six fascicles containing thirty-one chapters—this is the main text. The seventh fascicle has five chapters and contains offering rituals, like an appendix.

The Tibetan Translation

The Tibetan translation, during the time of Emperor Tri Ralpachan in the 9th century, was translated, edited and finalised by the Indian master Śīlendrabodhi and the great translator Bandhe Paltsek.

The Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana that exists in Tibetan has two parts: the root tantra and the later tantra. The first, the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana, has twenty-five or twenty-six chapters. The second, the Later Tantra Divided into the Stages of Supreme Secrecy [རྒྱུད་ཕྱི་མ་གསང་བ་མཆོག་གི་རིམ་པར་ཕྱེ་བ་།], has seven chapters.

Regarding how this very Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana was taught by the Teacher, according to what appears in Butön's General Exposition of the Tantra Classes [Tib. རྒྱུད་སྡེ་སྤྱི་རྣམ།]:

in Akaniṣṭha, Mahāvairocana in saṃbhogakāya form taught the Mahāyāna dharma;

on the peak of Mount Meru, Vairocana in nirmāṇakāya form taught the secret mantras through physical form;

and on Vulture Peak Mountain, Vairocana's nirmāṇakāya in the form of Śākyamuni taught the sūtras, the Lakṣaṇayāna [Vehicle of Characteristics] and so forth.

Specifically, this very Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana was taught by Mahāvairocana in Akaniṣṭha, in the buddha field of Vairocana, in the realm of Kusumatala Garbhavyūha Alaṃkāra. The questioner, the chief of the retinue, was Vajrapāṇi. Beginning from Vajrapāṇi's questions to Vairocana about bodhicitta, the method of generating it and so forth, the root tantra together with the later tantra was taught. This later tantra has no more than seven chapters. Butön in his General Exposition of the Tantra Classes states:

Though this does not appear in current editions, the later tantra is still not complete, because the passages cited from the later tantra in the commentary are incomplete.

He said that most likely because, in Buddhaguhya's commentary on the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana, some passages cited from the later tantra are not present in the Tibetan translation.

The portion corresponding to the first six fascicles of the Chinese translation was rendered into Tibetan in seven fascicles and twenty-nine chapters. Some scholars say that the Chinese seventh fascicle on offering rituals was composed by Śubhākarasiṃha himself. However, in the Tibetan version, the portion corresponding to the Chinese seventh fascicle is included in the Tengyur, and another person's name is written as the author.

The First Chapter

In the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana, the first chapter, called “Entering the Mantra Gateway and Dwelling in the Mind” [Ch. 入真言门住心品] is very important regarding philosophy, while from the second chapter onward primarily teaches the practices of maṇḍalas, mudrās, mantras and so forth. In the first chapter, the teaching is presented through the form of Vajrapāṇi Guhyapati [Vajrapani Lord of Secrets] posing questions to Tathāgata Vairocana about a method of attaining the wisdom of omniscience and the philosophical foundation. The famous three sentences:

The cause is bodhicitta, the root is great compassion, the ultimate is skillful means.

form the foundation of the first chapter and a very important statement of the entire The Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana.

The Emergence of the Abhisambhodhi of Vairocana

The texts

Contemporary scholars believe that certainly some tantric texts existed before the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana emerged. For example, previously translated into Chinese are the Dhāraṇī Collection [Tib. གཟུངས་བསྡུས།], the Ekākṣaroṣṇīṣacakra [Single-Syllable Sūtra of the Crest Wheel; Tib. གཙུག་ཏོར་འཁོར་ལོས་བསྒྱུར་བ་ཡི་གེ་གཅིག་མའི་མདོ།], the Susiddhikara Sūtra (Tantra) [The Sutra of Easy Accomplishments; Tib. ལེགས་གྲུབ་ཀྱི་རྒྱུད།], the Subāhuparipṛcchā Sūtra (Tantra) [The Sutra of Subahu’s Questions; Tib. དཔུང་བཟང་གིས་ཞུས་པའི་རྒྱུད།] and so forth. Additionally, texts translated into Tibetan such as the Empowerment of Vajrapāṇi Tantra and the Vajravidāraṇa Dhāraṇī [The Dharani of the Vajra Conqueror; Tib. རྡོ་རྗེ་རྣམ་པར་འཇོམས་པའི་གཟུངས།] are believed to have provided much material for the emergence of the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana.

The Time

The current universally accepted explanation is that the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana was composed in the mid-7th century based on the above texts. It is interesting to note that, in Xuanzang's travel records of his time in India until 645, nothing about tantra was written, but in the travel records of Wuxing who went to India around 685, it states: "Recently heard that the mantra teachings are greatly respected throughout the countries," and by this time Wuxing had obtained the manuscript of the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana. Therefore, considering the gap period when Xuanzang and Wuxing were not in India, it can be estimated that the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana emerged in the middle of the 7th century. Although, it could very well be that Xuanzang hasn’t written about it due to lack of interest and the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana emerged earlier than that.

The Place

Regarding where the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana originated, there are many opinions—some say it came from Nālandā in central India, some say from Lāṭa in western India, some prefer southern India, some prefer Kapiśa in present-day Afghanistan, and some prefer northern India. However, these opinions lack solid evidence. There is a strong possibility that it was composed at Nālandā, which was the center of Buddhist learning at that time, or in the western India region. In any case, it can be estimated that by the early 8th century, the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana had spread among the powerful Rājput tribes and mountain peoples of northwestern India.

Its Versions and Commentaries

According to Chinese and Japanese traditional teachings, there are believed to be short and long editions of the original Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana manuscript. Both the current Chinese and Tibetan translations are believed to be abbreviated editions extracted from an extensive sūtra of one hundred thousand verses in three hundred fascicles. This is written in the first fascicle of the Mahāvairocana Sūtra Commentary [Tib. རྣམ་སྣང་མངོན་བྱང་གི་འགྲེལ་པ།; Ch. 大日经疏] composed by the Tang master Yixing. Likewise, the Japanese tantric master Kūkai, in his Dainichi-kyō Kaidai [ 大日经开题] stated that, in addition to the long and short versions, there also existed a third one. However, other histories do not clearly testify to the existence of the long and short versions so contemporary scholars suspect it may just be faith and belief. Alternatively, looking at the various offering rituals, practice methods, and supplementary tantric texts, it is not impossible that an extensive edition could exist.

The only commentary on the Abhisambhodhi of Vairocana that exists in Chinese is the Mahāvairocana Sūtra Commentary, which was taught by the Indian master Śubhākarasiṃha and written down by Master Yixing. It has a total of twenty fascicles. The version edited by Zhiyan and Wengu, called the Mahāvairocana Sūtra Meaning Commentary [Tib. རྣམ་སྣང་མངོན་བྱང་གི་དོན་འགྲེལ།] has fourteen fascicles. These commentaries extensively explain the philosophy and practice methods taught in the text. Japanese tantric practitioners consider the earlier commentary primary, while those who hold the Tiantai [T'ien-t'ai] school view consider the later one primary.

As for the commentaries extant in Tibetan, there is a summary text of the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana written by the 8th-century Indian master Buddhaguhya and translated into Tibetan by the Indian master Śīlendrabodhi and Go Lotsawa Bandhe Paltsek. Another, extensive commentary called the Textual commentary on the Sūtra of Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana also written by Buddhaguhya is missing a colophon, so some scholars doubt his authorship of this version. The extensive commentary provides word-by-word explanations, and it has Tibetan editing and annotations. In the 15th century, Gö Lotsawa Zhönu Pal edited it.

Between the Chinese and Tibetan translations of the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana, there are slight differences in word order and the order of individual chapters. Additionally, in the quotations from the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana found in the two Chinese commentaries and Buddhaguhya's commentary, there are some discrepancies that, though not very obvious, do exist. This can demonstrate that since the initial compilation of the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana, multiple revisions were made. Not only that, but it can also be estimated that in China, not only Wuxing's manuscript but some other Sanskrit manuscripts also arrived.

In the Karma Kamtsang

In the biographies of the First Karmapa Dusum Khyenpa and Karma Pakshi and others that are currently accessible, there is no mention of them receiving the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana.

From the Autobiography in Verse [Tib. རང་རྣམ་ཚིགས་བཅད་མ་ལས།] of the Third Karmapa Rangjung Dorje:

In order to complete the dharma intentions

Of the great master, glorious Orgyenpa,

From the spiritual friend Kunga Drubchub

I received the Kālacakra Tantra [The Wheel of Time Tantra], commentaries, and branches,

Māyājāla [The Net of Illusion] and the Tamer of Spirits,

Mahācakra [The Great Wheel], the Sampuṭa Tantra and commentary…

It also says: “Uṣṇīṣa Vijaya, Vairocana and Net of Illusion..."

The Golden Garland of Kagyu Biographies states: "Uṣniṣa-vijaya, the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana and the Net of Illusion with empowerments." Rangjung Dorje's phrase "Vairocana Net of Illusion" [Vairocana Māyājāla] is separated out, applying "Vairocana" to the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana and "Illusion" [Māyā] to the Net of Illusion [Māyājāla].

This is because there are three commonly known Nets of Illusions: the Mañjuśrī Net of Illusion, Vairocana Net of Illusion and Vajrasattva Net of Illusion. Whether the Vairocana Net of Illusion mentioned by Rangjung Dorje in his autobiography refers to the commonly known Vairocana Net of Illusion, or whether, as Situ Chokyi Jungne stated, "Vairocana" refers to the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana and "Net of Illusion" to a different tantra, is not clear.

If, as Situ Rinpoche stated above, Rangjung Dorje did receive the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana, then it appears that the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana was first transmitted to the Karma Kamtsang during the time of Chöje the Third Karmapa, Rangjung Dorje.

At any rate, the sixth Karmapa Thongwa Donden received the the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana from Zhalu Chandrapa, or Dawa Pal, who was a student of Butön's student Dratsepa Rinchen Namgyal and others. Based on this, an independent lineage of the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana spread in the Karma Kagyu.

In the biographies of the Golden Garland of the Kagyu (Tib. བཀའ་བརྒྱུད་གསེར་ཕྲེང་།), in the biography of Thongwa Donden, it states: "From Rinpoche Dawa Pal he received the empowerments of Vajra Peak condensed lineage [Tib. རྩེ་མོ་རིགས་བསྡུས།], Śrīparama [Glorious Splendour] condensed lineage [Tib. དཔལ་མཆོག་རིགས་བསྡུས།], Trailokyavijaya [Victory over the Three Worlds; Tib. ཁམས་གསུམ་རྣམ་རྒྱལ།), Uṣṇīṣavijayā [Tib. གཙུག་དགུ་འཆི་འཇོམས།], Vajra Expanse, Amoghapāśa [Unfailing Noose; Tib. དོན་ཡོད་ཞགས་པ།], the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana, Pañcarakṣā Dhāraṇī (Dharani of Five [Female] Protectors; Tib. སྲུང་བ་ལྔའི་རིག་གཏད།), Śaṃvarodaya [The Arising of Shamvara; Tib. བདེ་མཆོག་སྡོམ་འབྱུང་།], the combined: སྒྱུ་ཐོད་གདན་གསུམ, The Five Deities of Ghaṇṭapada; [Tib. དྲིལ་ཆུང་ལྷ་ལྔ།], The Lord of the World of the Lineage (Tib. རིགས་ཀྱི་འཇིག་རྟེན་མགོན་པོ།), Avalokiteśvara Padmajāla [Avalokiteshvara Net of Lotuses; Tib. སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས་པདྨ་དྲྭ་བ།], the Maṇḍala of Tārā’s Body [Tib. སྒྲོལ་མ་ལུས་དཀྱིལ།], Guhyasamāja [Secret Assembly] according to Nāgārjuna's system; [Tib. འདུས་པ་ཞབས་ལུགས།], Guhyasamāja Avalokiteśvara, Vajrapāṇi Mahācakra [The Great Wheel of Vajrapani; Tib. ཕྱག་རྡོར་འཁོར་ཆེན།), Ṣaṇmukha (Six-Faced; Tib. གདོང་དྲུག།) and the reading transmissions of various Prādipoddyotana [Brilliant Lamp; Tib. སྒྲོན་གསལ།].

"At that time, many Geluk rituals were established at Karma Gön. When he sat at the head of the row in a puja, he asked why. Drung Rinpoche replied, ‘We don’t have our own texts.” Tongwa Donden replied, ‘I can write the rituals’ and the sādhanā and maṇḍala ritual of the Vajra Expanse, the Sādhanā of the Body Maṇḍala of Saṃvara [Tib. སྡོམ་པ་ལུས་དཀྱིལ་གྱི་སྒྲུབ་ཐབས།], the sādhanā of Vajrayoginī, the Ocean of Victors and others that appear in the Collected Works [Tib. བཀའ་འབུམ།]. He newly composed the drum dances and melodies of Mahākāla and so forth, conferring them as additional deity practices."

It is also stated that he wrote the maṇḍala ritual of the Vajra Expanse, called the Delight of the Fortunate Aeon [Tib. ཆོག་སྐལ་བཟང་དགའ་སྐྱེད།], at the request of Goshir Paljor Dondrub, Jampel Zangpo, and others.

Thongwa Donden definitely passed them to Goshir Paljor Dondrub and Pengar Jampel Zangpo. In the biography of Sangye Nyenpa Tashi Paljor, composed by Je Mikyo Dorje, entitled Sangye Denma Chenpo [Tib. སངས་རྒྱས་འདན་མ་ཆེན་པོ།], regarding how Sangye Nyenpa received The Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana from Goshir Paljor Dondrub, it clearly states: "From Bodhisattva Paljor Dondrubpa he received the empowerments and reading transmissions of Ḍākārṇava [Ocean of Dakas; Tib. མཁའ་འགྲོ་རྒྱ་མཚོ།], Cakrasaṃvara of Luyipa, Nakpopa and Drilbupa, the Three Lineages of Hevajra (Tib. དགྱེས་རྡོར་བཀའ་བབས་གསུམ།), Concentrated [Practice of] Hayagrīva’s Heart; [Tib. རྟ་མགྲིན་ཐུགས་དྲིལ།], Peaceful and Wrathful Gurus [Tib. གུ་རུ་ཞི་དྲག།], Mahākāla, Ocean of Victors and Vārāhī [Tib. ནག་རྒྱལ་ཕག་གསུམ།], Thongwa Donden's Amitāyus in Three Aspects—Outer, Inner and Secret [Tib. ཚེ་དཔག་མེད་ཕྱི་ནང་གསང་གསུམ།], Mahāmāyā [The Great Illusion; Tib. མ་ཧཱ་མཱ་ཡཱ།], the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana, the All-Knowing Vairocana, Akṣobhya [Tib. མི་འཁྲུགས་པ།] and so forth."

Mikyo Dorje also received [these teachings] from Sangye Nyenpa. Although not stated clearly in the Feast for Scholars [Tib. ཆོས་བྱུང་མཁས་པའི་དགའ་སྟོན།], it can be concluded based on the statement: "he matured [students] by conferring empowerments in the principal maṇḍalas of the four tantra classes."

In particular, Je Mikyo Dorje newly composed a sādhanā and maṇḍala ritual for the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana entitled The Smiling Crescent Moon [Tib. ཟླ་ཚེས་འཛུམ་པ།]. This appears to be the sole text, or at least among the earliest, of a sādhanā and maṇḍala ritual for the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana in the Karma Kagyu tradition.

Therefore, the conferral of the empowerment of The Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana by Drung Gyaltsab Rinpoche at this time is in accord with the biographies of how Drung Thongwa Donden previously conferred the empowerment of the Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana on Goshir Paljor Dondrub, and how Goshir also spread that empowerment Sangye Nyenpa Drubthob and to others.

The Abhisaṃbodhi of Vairocana that Rinpoche will confer was transmitted from Bari Lotsawa to the Kadampas, then from Butön to Dratsepa Rinchen Namgyal and to Zhalu and Sakya. From there it was also transmitted to the Gelug masters such as Darhan Choje Yeshe Drakpa, the second Jamyang-zhepa Jigme Wangpo, Jamyang Tubten Nyima, Drakgompa Tenpa Rabgye, and others.

From Drakgompa Tenpa Rabgye it was transmitted to the Sakyapa Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo, and Jamgon Lodro Taye also received it from Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo. However, it appears that Jamgon Rinpoche did not particularly propagate it.

Later, on the Sakya side, the eighteenth Trichen Rinpoche was a principal propagator of the empowerment cycle of the Complete Collection of Tantra Classes [Tib. རྒྱུད་སྡེ་ཀུན་བཏུས།] (The Ocean of Tantras).

In his biography The Way Into Faith [Tib. དད་པའི་འཇུག་ངོགས།], it states: "At that time, when his attendant Lama Guru came to his chambers, Rinpoche was unusually joyful and, while performing the vase-water ritual, said: 'Today His Holiness Sakya Gongma Rinpoche came here and asked me to confer the empowerment of The Ocean of Tantras [Tib. རྒྱུད་སྡེ་ཀུན་བཏུས་]. At first I did not agree. However, Rinpoche was very insistent. Previously, Khangsar Khenpo Rinpoche and others possessed that empowerment lineage, but nowadays Khenpo Rinpoche has passed away, so that empowerment lineage exists only with me. Therefore, in the end I had to agree to offer that profound Dharma teaching to Sakya Tridzin.'

And: 'Actually, the previous year at Phakpa Shingkun, when the sixteenth Karmapa Rangjung Rikpe Dorje conferred the Treasury of Precious Instructions [Tib. གདམས་ངག་མཛོད།], I attended. At that time, he affectionately patted my shoulder with his hand and said, "Rinpoche, later Sakya Tridzin will request The Ocean of Tantras from you. Don't refuse at that time! I also plan to send some tulkus to request teachings." This was clearly a prophecy. How wondrous!'

He said: 'This year we do not need to stay in the heat of Lumbini. We must go to India where His Holiness Sakya Tridzin Rinpoche resides.' "

From then on, for three successive years he traveled annually to the Dharma encampment of Pal-sakya in India to confer the teaching and empowerment of The Ocean of Tantras just as he had received them from Je Lama Ngor Khangsar Khenchen Dampa Dorje-chang Ngawang Lodro Zhenpen Nyingpo—the unbroken empowerment, reading transmission and instruction lineages of the vast precious tantra classes, the pinnacle of the vehicle, through the tradition of the Eight Great Practice Chariots that spread in Tibet—with great compassion came to the noble land of Rajpur, to the Sakya Dharma encampment, on the fourth day of the twelfth month of that year, and conferred the complete empowerment, reading transmission and instruction lineages of the precious The Ocean of Tantras over three years, tirelessly, with Kyabgon Gongma Rinpoche presiding, to the great monastic seats of Pal-sakya—Sakya, Ngor, Tsar and Dzong—the khenpos, lama-tulkus, chief ritual masters, permanent residents and hundreds of monks who came from various places.

After the teaching was successfully completed, Kyabgon Sakya Tridzin Rinpoche with great delight offered a long-life ceremony to this master, whereupon the eighteenth Rinpoche said: 'Now the Dharma has reached its rightful owner, so I am content.'"

How the Sixteenth Gyalwang Karmapa Received The Ocean of Tantras

On one auspisious occasion, when we invited the Lord of Refuge Kyabje Sakya Trichen Rinpoche to the 32nd Kagyu Monlam, he gave a talk and shared how he visited the Sixteenth Gyalwang Karmapa, who he was very close with, in the hospital in Delhi. This was not long after Sakya Tridzin had received the empowerment, and the Sixteenth Karmapa said: “It is truly wonderful that you have been able to receive these empowerments of the Ocean of Tantras. In the future, there are a few tantras we need to add and please bestow them, including the supplementary texts.”

Therefore, this amazing opportunity for receiving the empowerment of the Abhisambodhi of Vairocana from the Ocean of Tantras, is in accord with he wishes of the Sixteenth Karmapa and this is a great way for us to serve him. Prior to his arrival, Gyaltsab Rinpoche returned to his monastery and entered a seven-day retreat—just as he did when he received the empowerment—thus, once again, devoting great care to the event. As this is, historically, a very precious opportunity and truly auspicious time for all of us, the Karmapa advised the attendees to please approach the empowerment with great faith.